The saying goes “if at first you don’t succeed, try again.”

I did. And failed worse.

I had just taken the entrance exam for business school, the GMAT. My future lay with the three digit score presented on screen. My heart sank. The score was too low. Worse, this was my second attempt at the exam. Even worse, my score was lower than my first attempt. I sat in stunned horror.

I had tried again. I had worked harder, longer, and smarter.1 And I went backwards. Such an outcome seems laughably impossible. We don’t workout at the gym and see our muscles get weaker.

“The data doesn’t lie,” trendy business wisdom states. My exam scores told the truth. I didn’t have the talent for business school. I accepted the fact and moved on with life.

We’re each born with innate strengths. Some of us are more creative, athletic, logical, or whatever. We’re then advised to do what we’re good at. We’re happiest when we lean into those talents for success.

Years after my experience, I began to think maybe I could score well enough on the GMAT. In a bout of inspiration, I signed up for a study course. I prepared to take the exam again. After yet another round of many months of studying, I took the GMAT for a third time. I scored what I needed. I attended business school.

I was elated, of course. Yet a bit confused. I went from clear signals I couldn’t score well, to actually scoring well. Was I wrong about myself? Did I change? Surely, I was the same person?2

I dove deeper into the research around human achievement. Turns out I viewed talent and achievement wrong.

Talent is overrated

“Oh they’re so talented!”

I had received a video of young relative sent to a family group chat. The child demonstrated exceptional athletic ability, navigating an obstacle course with ease. Messages gushing over the child’s ability poured in.

Starting with children, we make assessments on a person’s innate talent. When a person is gifted with such talents, we nurture with effort and hard work. Together, this flourishes to success and achievement.

We assume: talent x effort = achievement

However, we miss a crucial piece - skill is applied for achievement. And we aren’t born with skill. Talent is what we’re born with. Skill is what we develop.

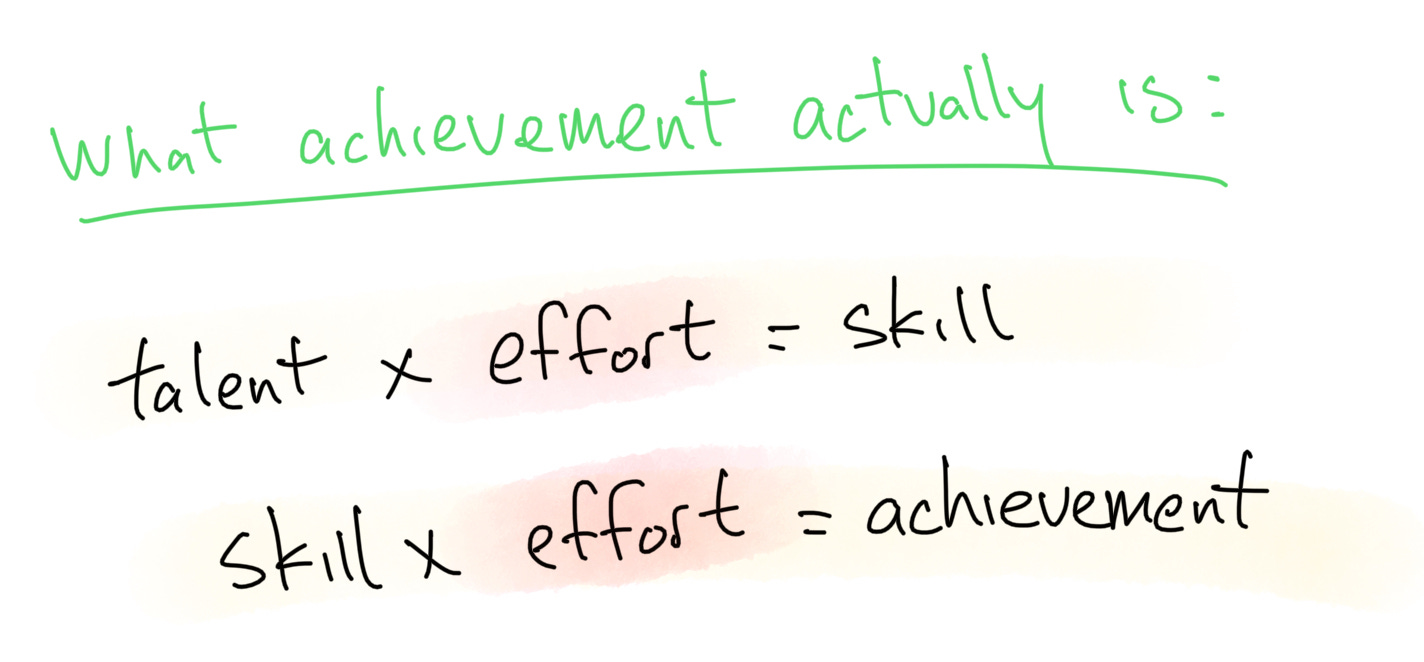

Researcher Angela Duckworth explored the link of talent and achievement.3 Duckworth and her colleagues found achievement can be represented as 1) the development of skill, and 2) the application of skill:

talent x effort = skill

skill x effort = achievement

These statements are profound.

First, regardless of innate talent, we can develop skill. Lower talent and higher effort can reach the same result as higher talent and lower effort.

Second, effort is necessary to acquire skill. Talent is nothing without effort. Examples abound whenever we speak of “wasted talent,” suggesting an innate talent has not been harnessed.

Third, effort counts twice for achievement. Talent is only a starting point. It’s also a minor contributor. Effort has an outsized contribution to achievement and success.

Effort is also something we have greater control over. In other words, we have much more control over our success and achievements than our talents suggest.

What contributes to talent or effort?

Talent is most associated with traits relating to how our brain processes the world - cognitive ability, creativity, intelligence. Effort is most associated with how we apply our brainpower - zest, self-control, curiosity. While we’re born with an innate set of traits, both talent and effort traits are malleable (a fascinating domain unto its own, not addressed here).

What if we’re not talented?

When we feel untalented, we feel demotivated to achieve. Sure, we could work harder and longer. But that feels like a recipe for burnout.

Surprisingly, for the highest level of performers, excellence is not grueling and painful. Researcher Daniel Chambliss studied Olympic swimmers to understand their success. He found a counterintuitive result. Excellence is mundane.4

World class swimmers studied did not possess a special inner quality, whether physical or mental. The process towards excellence is mundane. Excellence was a result of many ordinary actions, compounded over time. The psychology is also mundane. There weren’t the emotional highs and lows we’d expect at an elite level of competition. Rather, swimmers operated in a state of contentment and focus, viewing big and small with the same “just another swim meet” mindset.

Chambliss sums up his research - “talent is a useless concept.”

“People don’t know how ordinary success is”

- Mary Meagher, 3 time Olympic gold medalist

What can we do to achieve more?

So effort matters the most. Excellence is mundane. Talent is overrated. There are many factors and tactics to achieve goals. Here are just a few ways to shift our mindset and put these principles to work:

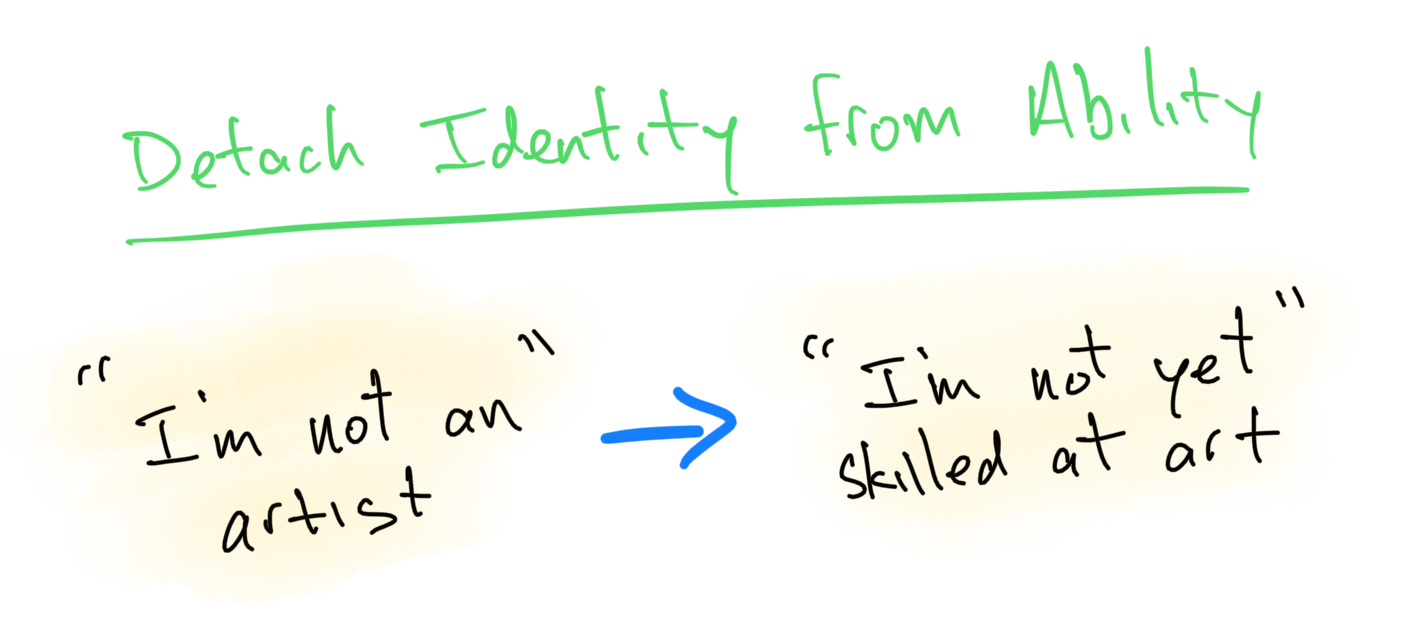

Detach talent and skill

We tie our identities to our talents. Statements such as “I’m not an artist” or “I’m not a numbers person” harden our beliefs. However, if we detach our identity from our skills we change what’s possible. Our identity does not define our abilities. Rather, we choose our abilities. We move from “I’m not an artist” to “I’m not yet skilled at art.”

Do little things well

We look at grand achievements of the skilled and think we could never do what they do. But achievement isn’t a singular large success. Achievement is a cumulation of small actions and successes. It just looks like a grand achievement to the casual observer.

Legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden would start the very first team meeting of the season with a demonstration of how he wanted players to put their socks on.5 He'd demonstrate, then watch as each player practiced the process. Small wrinkles or bunches in socks could lead to painful blisters after hours of play. Break ambitious goals into tiny wins, done well.

“I believe in the basics.. They may seem trivial, perhaps even laughable to those who don’t understand, but they aren’t. They are fundamental to your progress in basketball, business, and life.”

- John Wooden, former UCLA basketball coach

Enjoy the process

Skill and achievement occur over the long run. Expert swimmers did not view practices as the price to pay for the reward of winning. Rather, the swimmers reported enjoyment in the regular aspects of their training. They enjoyed the social aspect of spending time with friends. They enjoyed the simplicity of time in the water. Motivation for the long term comes from enjoyment in the mundane of the everyday. Small wins motivate for the long term.

..And therefore what?

Achievement takes time. Effort is hard. No doubt the path isn’t easy.

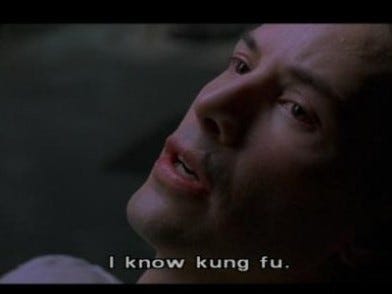

In the film “The Matrix,” the main character Neo can know any skill desired via “uploads” to his mind. There is no limit to what skill Neo can possess, he just just chooses and uploads the information. Whether that’s the ability to pilot a helicopter or fight hand to hand combat.

In our world, instant upload of skill doesn’t exist. But we too, can choose our skills. And what we choose from is endless as well.

We move beyond just thinking “what am I good at?” to “what do I want to be good at?”

The more we dissolve the myth of talent, the more we create opportunity for achievement.

Corporate management wisdom tells us the secret of our success - “don’t just work harder, work smarter.” Wait, are you saying I’ve been unsmart all along?

My friend and roommate at the time can attest to my character while I was in study mode - I was consistently an anti-social and unfun person to be around. Thanks, Pat!

Duckworth, Angela L., Johannes C. Eichstaedt, and Lyle H. Ungar. "The mechanics of human achievement." Social and Personality Psychology Compass 9.7 (2015): 359-369.

Chambliss, Daniel F. "The mundanity of excellence: An ethnographic report on stratification and Olympic swimmers." Sociological theory 7.1 (1989): 70-86.

Wooden, J. (1997). Wooden: A Lifetime of Observations and Reflections On and Off the Court. Ukraine: McGraw Hill LLC.

When I was kid, all I saw was talent bc kids don’t haven’t had time yet to put in sustained effort. That led me to believe that talent was super important to success. The smart kids - those were the ones would be successful. It was genetic lottery. I felt like I was in that group too - got good grades and went to Columbia.

As I got older, I saw career outcomes for smart kids and not smart kids diverge.

Now I believe that sustained, focused effort is 90% of success. What I observed as a kid was relative talent differences. Compared to a frog, all people are nearly identical in absolute talent. The only difference between people is how they spend their limit processing power, not how much processing power they have.

TL; DR if you can figure out what you really want to be good at, you can be in the top 10,000 people in the world for that thing regardless of talent.

The real challenge is figuring out what we should focus on.